Painting Pictures and Making Games with a Watercoloring Robot

30 Nov 2017I’m spending the 2017-18 school year volunteering in a few tech classes in a local high school, including a beginner/intermediate Python course led by a teacher named Tamara O’Malley. She’s new to Python, and I have a lot of experience with the language, so I’ve been helping her come up with fun projects for the students to work on.

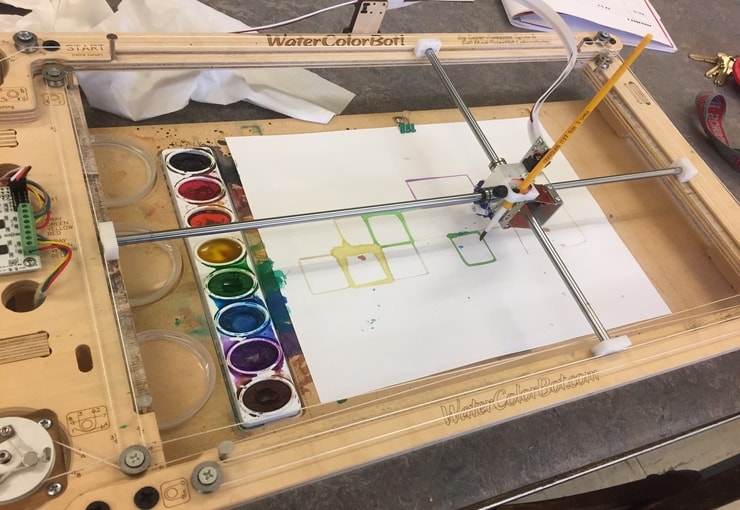

When we started talking about potential projects, Tamara mentioned that she had a WaterColorBot that she’d like to have the students use in some way. Here’s a picture from its official website:

She’d already had a lot of success using the bot in another intro-to-programming course via a block-based language called Snap, but she wasn’t sure how to talk to the bot via Python.

This sounded like a fun project, so I looked into it. It turns out that there are lot of great ways to drive the bot via software, but I couldn’t find anything Python-based that did what we wanted. I came up with a few possible approaches and asked Windell Oskay for advice, and he kindly set us on the right track — thanks, Windell!

madison_wcb

I ended up writing a library called madison_wcb to solve our problem. (This library was easy to write, thanks to the excellent and well-documented “Scratch API” that the bot supports.)

The library lets students write code like this:

# Dip the brush in the palette's top-most color.

get_color(0)

# Move the brush to the mid-right side of the page, "face" directly

# "south", and lower the brush so that it touches the paper.

move_to(100, 0)

point_in_direction(-90)

brush_down()

# Paint a circle!

for i in range(360):

move_forward(2)

turn_right(1)

If you’ve got a WaterColorBot lying around, you can use this library too! Just check out the documentation or source code and go nuts.

Here’s one student’s program in action:

The library also uses Python’s built-in turtle module to show you what your program will do.

This saves users a lot of potential frustration, and also a bunch of paint.

Perhaps Somewhat Impractical

To be honest, this library is a pretty insane way to control the bot. It’s needlessly low-level: you’re manually controlling the brush’s position, you’ve got to remember to wash and re-ink the brush every so often, etc. If your main goal is to just get the bot to paint a pretty picture, there are lots of better ways to go about it.

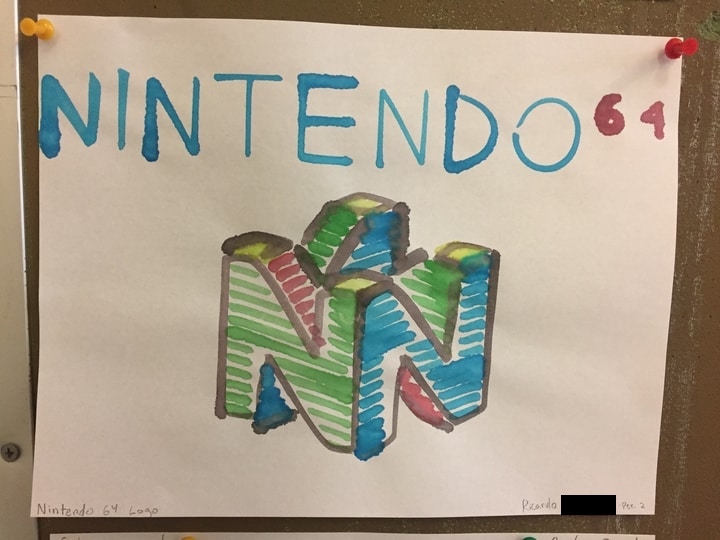

As a teaching aid, though, it’s been a total success, because it lets students flex their burgeoning Python skills and actually make a real thing in the process! We’ve been blown away by the stuff our students have created. Here’s an N64 logo in seven hundred and fifty hand-crafted lines of Python:

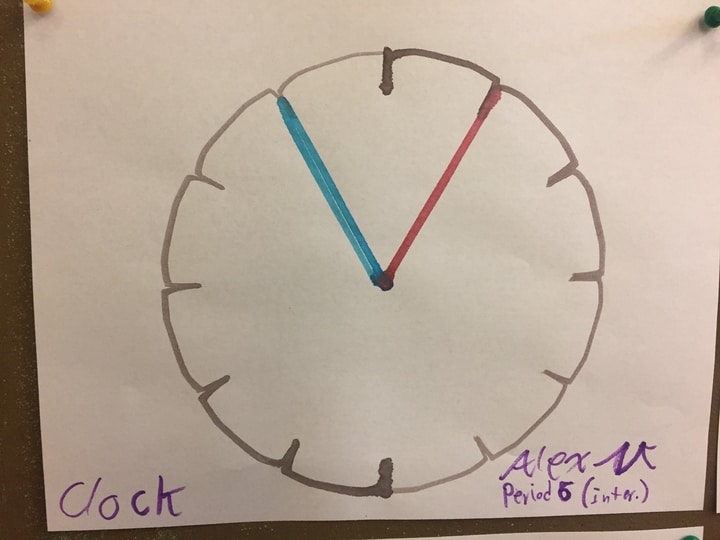

This clock depicts the time at which the program was run:

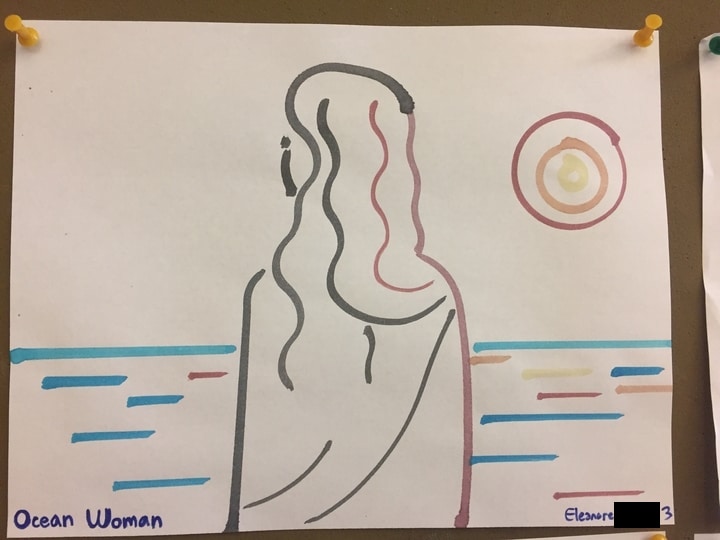

This student drew her image from scratch in Paint or something, using only straight lines and simple curves so it would paint well on the bot, and then translated it into Python:

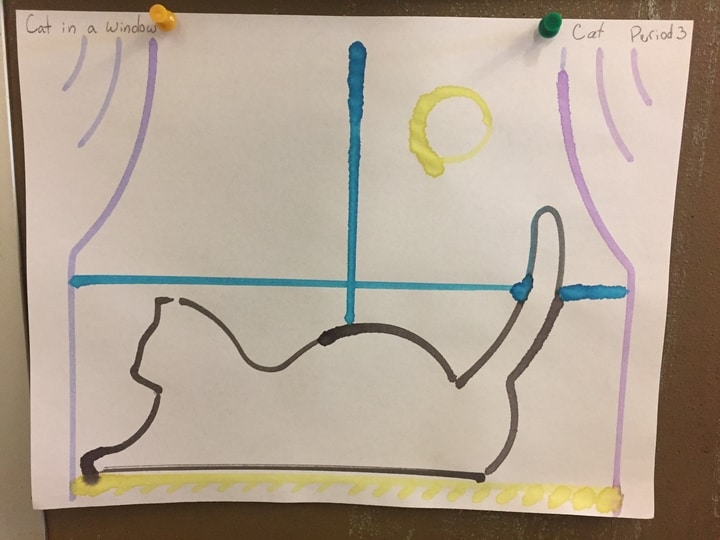

And here’s a nice windowsill cat.

These kids haven’t yet learned how to use lists/dicts or how to make their own functions, and they’re already making cool programs like these!

Interactivity

Once I finished writing the library, I thought it might be fun to use the bot as a “display” for a video game. As a proof of concept, I wrote an embarrassingly basic text adventure that uses the bot as a mini-map, painting in new rooms as you wander around the game world.

My favorite part about it is that once you’ve beaten the game, you end up with a completed map: a (slightly splotched) physical artifact that serves as proof of your victory.

If you’re interested in making a game that runs on a watercoloring robot, here are some design constraints to keep in mind:

- You’ve got an extremely finite amount of screen real estate (one page of printer paper)

- If you want to e.g. start a new page every level (maybe you’re writing a dungeon-crawler?), the user has to fiddle with the machine for ten seconds to take off the old page and ensure there’s a fresh page ready to go, which could get irritating over time

- You probably don’t want to paint on the same “pixel” twice (although I can imagine situations where an intentionally smudged page could make for a cool aesthetic)

Anyway, I thought the idea of an interactive watercolor program was interesting, so I showed the text adventure to the students. A few of them liked the idea and made their projects interactive too. Here’s me losing at one student’s Minesweeper:

This student has never used a two-dimensional array before, and he wrote a fully-functioning version of Minesweeper that runs on a watercoloring robot.

For this program and a few others, we decided to swap out the paints and paintbrush in favor of a pen. This allows for a lot more precision when drawing a grid or text/numbers, because if you try to do small fiddly motions on the bot with a paintbrush equipped you tend to just get an aimless splotch of paint.

Drawing text/numbers on the bot is kind of a hassle in general and can make for a visual mess, so I thought it was really clever that this student used domino-style dots in order to indicate how many mines are adjacent to a particular square. A small X on an individual square means “you’ve checked this square and there weren’t any mines nearby.”

Here’s another student’s implementation of Go:

We didn’t want to stop the game after every move to swap out pens, so his program represents white pieces as squares and black pieces as triangles.

Lessons Learned

I’ve been programming for a long time, but this was my first time writing code that controls a physical object. At first I was worried that a bug in my library could e.g. cause the three-hundred-dollar bot to rip itself apart, but Windell assured me that the bot’s “Scratch API” handles bounds checking automatically, and so that’s turned out not to be an issue.1

One thing we didn’t foresee was that our paints kept getting dirty, because students’ rough-draft programs often didn’t wash the brush frequently enough — for instance, you may have noticed that the solar system program from earlier in this article depicts an unusually brown sun. We went through a few palettes before solving this problem by setting aside a “production” palette, which we only swap in when we’re painting a student’s known-good, final-draft program.2

We also learned the hard way that it’s important to remove the bot’s water trays and paints whenever you equip the robot with a pen. Whoops.

That’s All For Now

We’ve still got plenty of school year left, and I can’t wait to see what crazy antics these kids get up to in future projects!

BTW: If you’re a programmer interested in volunteering in a high school coding class, check out TEALS, it’s how I originally got involved with this school.

-

If

madison_wcbdoes kill your bot, I’m very sorry. Use at your own risk 😕 ↩ -

I can’t find the exact quote, but when I mentioned this in my friends’ IRC channel, one of them had a quip like “good programmers always separate stage and production”. ↩